(image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Abstract:

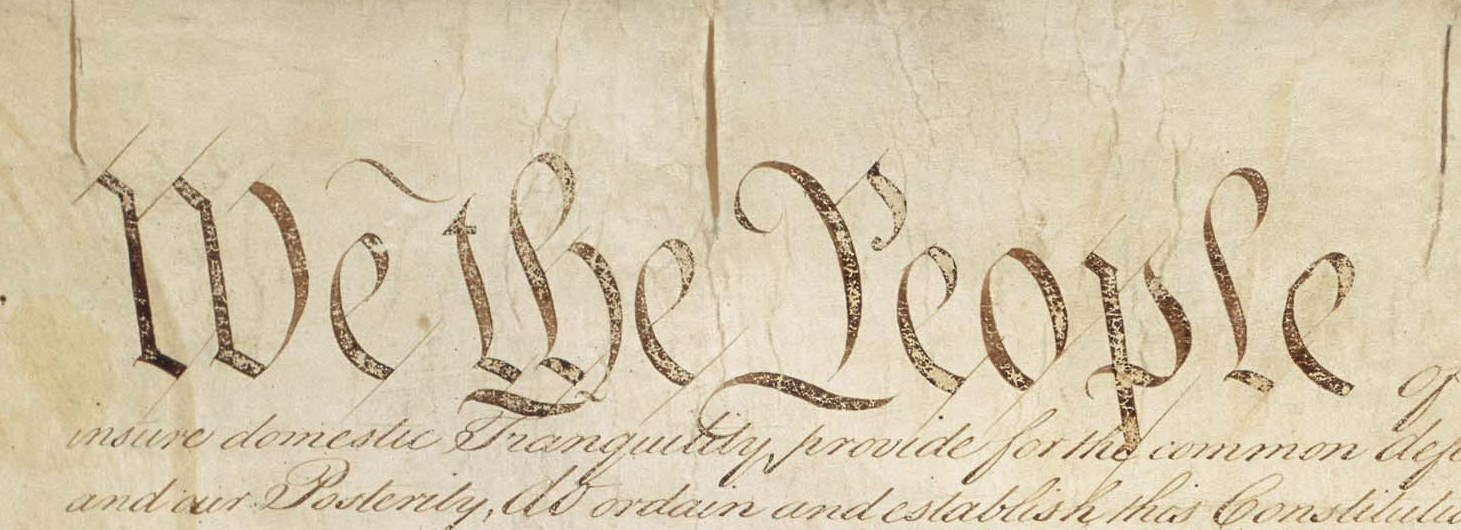

The Constitution was written in the name of the “People of the United States.” And yet, many of the nation’s actual people were excluded from the document’s drafting and ratification based on race, gender, and class. But these groups were far from silent. A more inclusive constitutional history might capture marginalized communities’ roles as actors, not just subjects, in constitutional debates. This Article uses the tools of legal and Native history to examine how one such group, Indigenous peoples, argued about and with the U.S. Constitution. It analogizes Native engagement to some of the foundational frames of the “Founding” to underscore its significance for current constitutional discourse. Like their Anglo-American neighbors, Native peoples, too, had a prerevolutionary constitutional order—what we here dub the “diplomatic constitution”—that experienced a crisis during and after the Revolution. After the Constitution’s drafting, Native peoples engaged in their own version of the ratification debates. And then, in the early republic, Native peoples both invoked and critiqued the document as they faced Removal. This Article’s most important contribution is proof of concept, illustrating what a more inclusive constitutional history might look like. Still, some of the payoffs are doctrinal: broadening the “public” in original public meaning, for instance. But the more significant stakes are theoretical. As this Article contends, by recognizing Indigenous law and constitutional interpretations as part of “our law”—in other words, the pre- and post-constitutional legal heritage of the United States—Native peoples can claim their role as co-creators of constitutional law.

Read the paper on SSRN.

No comments:

Post a Comment